“Chronograms of Architecture” is an exhibition organized by Jencks Foundation at The Cosmic House and e-flux Architecture with the Architectural Association. It began with a simple prompt – What is the contemporary relevance of Charles Jencks’ evolutionary diagram of architecture culture, first published in the 1970s (and revisited at several points in the twentieth century) to describe his characterization of contemporary architecture culture. This was an interesting question for me as I remember the ubiquity of this image in architecture schools of the 1990s when Rem Koolhaas’ use of architectural diagrams inspired many to emulate historical precedents. Given my recent studies of the racial epistemologies established by biological metaphors for design, I revisited Jencks’ diagram to contemplate the teleological models of history that underwrites his portrait in the field.

I reached out to Curry Hackett, an extremely talented architect and critic to create a triptych of images for the exhibit. We decided upon a dual strategy of implementation where I would provide a set of base diagrams that would characterize the racial epistemology of architectural tectonics, and he would visualize this in a visual history of the primitive tropes that expropriated Black material culture for use within architectural discourses. For my part, I was interested in emulating the stark clarity and essentialism of Jencks’ Cartesian approach to mapping architectural movements. Upon closer inspection it is clear that Jencks attempts to subvert a reductive interpretation of the field by charged language to describe the social implications of a particular movement. As an example, one can find the phrase “blood + soil” and “racist” under Fascist architecture movements of the 1940s. This explicit call out of the social mission of far right totalitarian regimes is fair and good from my perspective. Yet there is no equal call out of Eugenic tendencies, even amongst social progressives in the 1920s and 30s. (One only finds the single term of “streamline” to reference these practices underneath Frank Lloyd Wright’s name under Utopian approaches.) Nor is there any indication that some of the “Biomorphic” approaches outlined in the 1990s rehearsed similar essentialist language, especially amongst theorists of neo-organicism and emergence ideals. Of course, Jencks’ diagram was only meant to be a snapshot, but its status as an iconic summation of the past has encouraged its viewers to treat it as more than that–as a total summary of all that matters in architectural discourses. So, how might things have been different if we had a staunch critique of racialist thinking in architecture theory? What types of diagrams might emerge if we could employ the same Cartesian clarity to identify the implicit biases introduced through biological and anthropological borrowing? This was the primary motivation of my contributions to this exhibit.

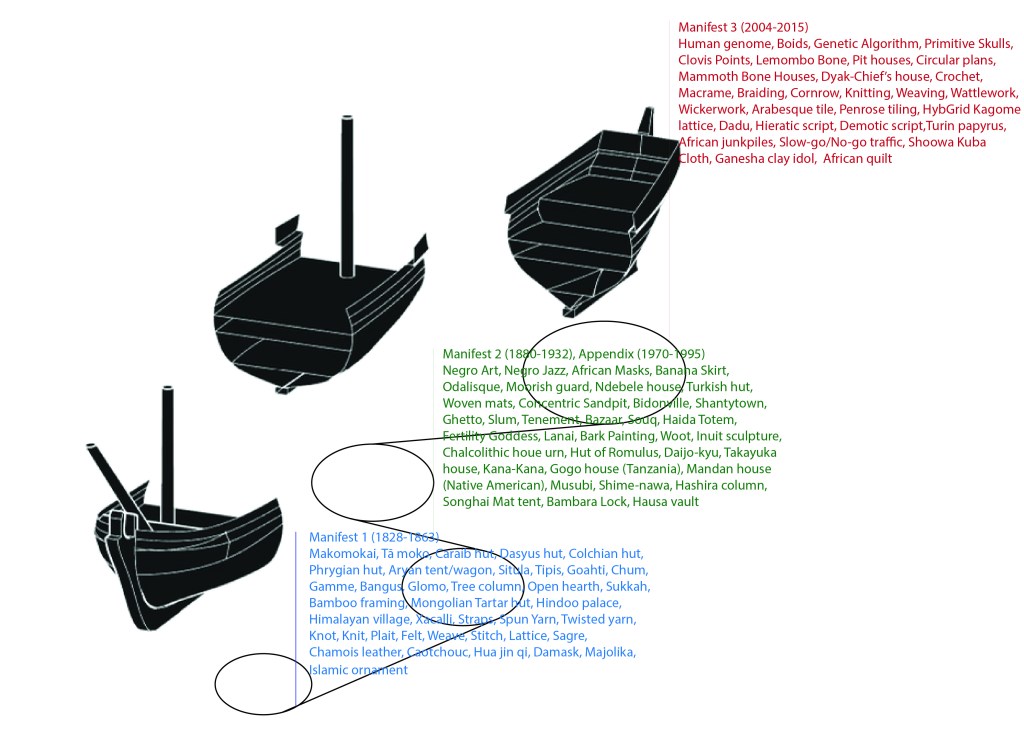

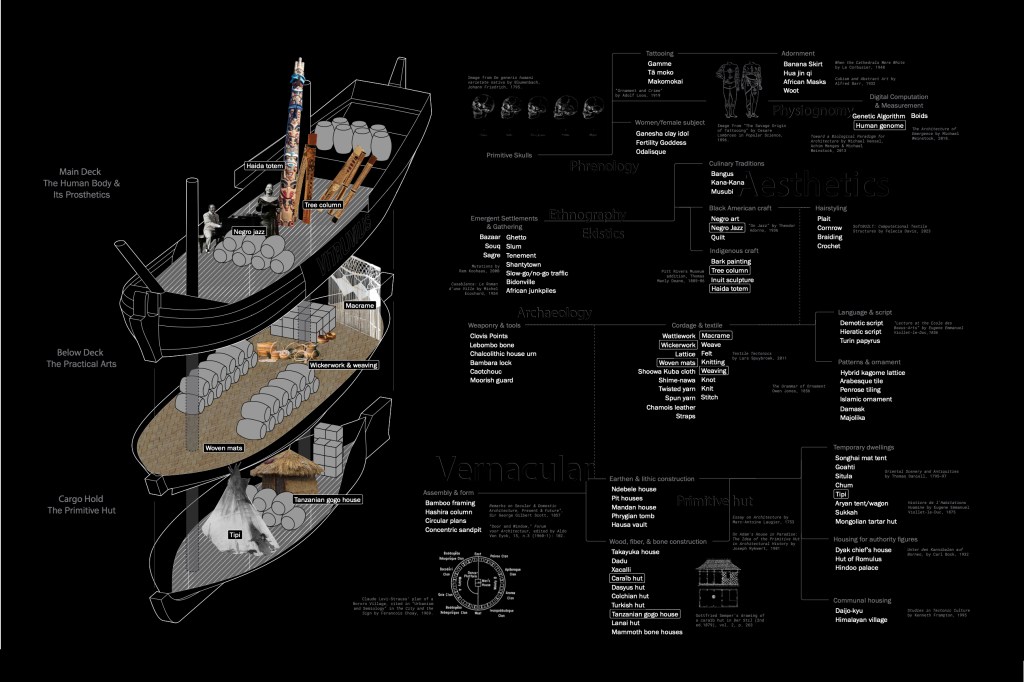

I began with a literal image of a slave ship being transformed into a skyscraper, with images of Black material culture being extracted as displays in the building section:

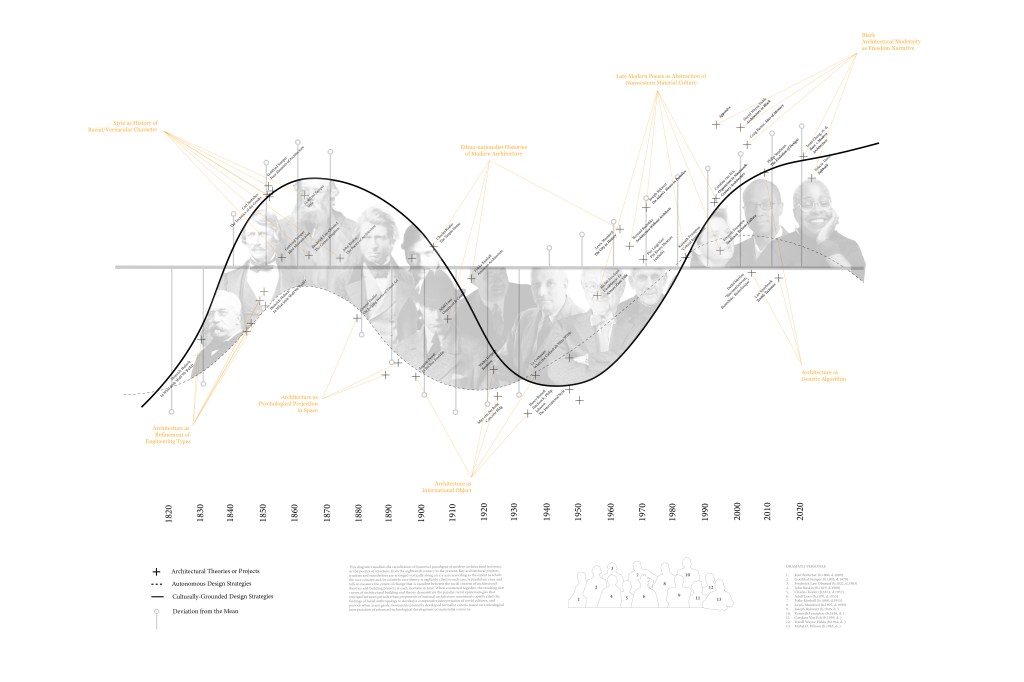

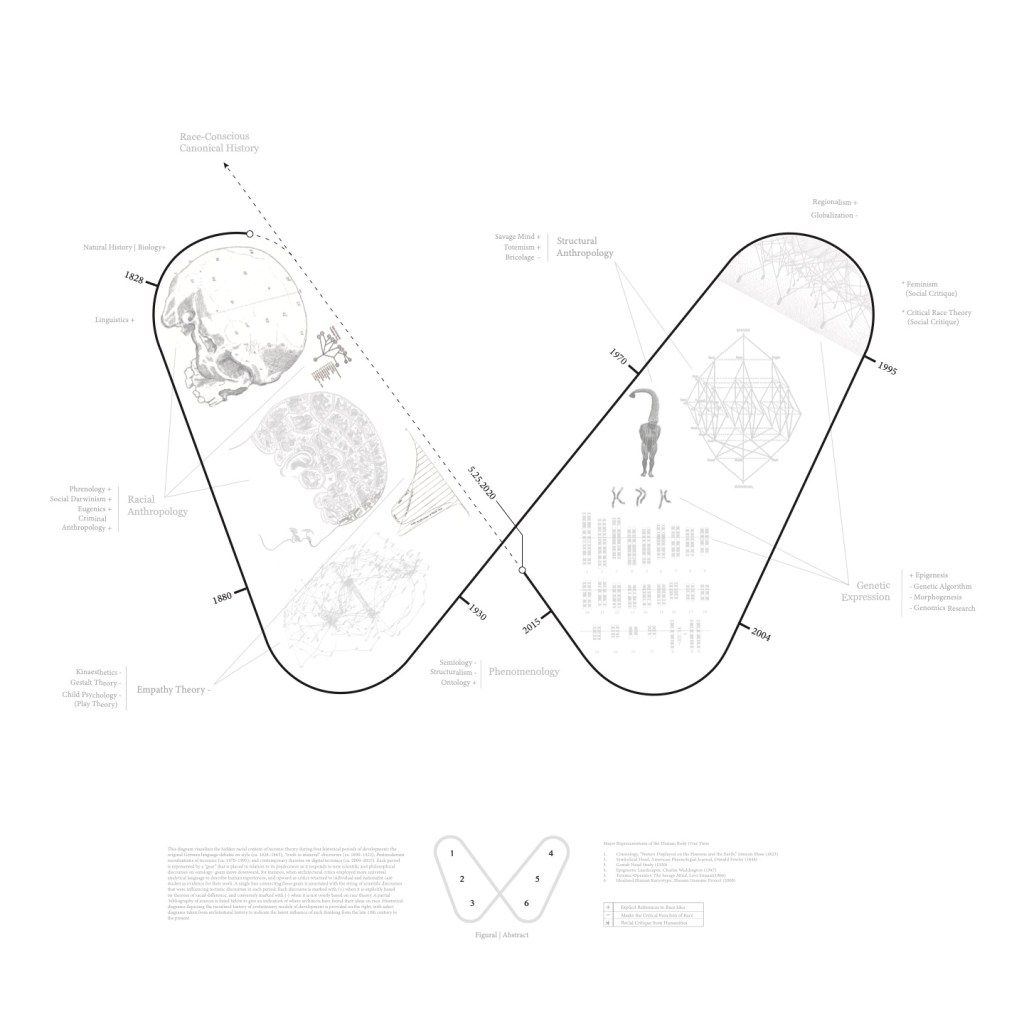

This approach gave way to a more diagrammatic approach used in a series of relational studies, shown here:

These were refined into the final two images for the exhibit, shown below:

Given these motivations, a few things needs to be said about my own biases and assumptions were while completing this work:

First and foremost, none of my research is interested in identifying whether any individual person is a ‘racist’ or not. I find those conclusions to be reductive and immaterial on their own (even though people will make such assumptions of my work as they did of Jencks’ diagrams). What is of greater importance, to me at least, is whether the specific discourses an architect or designer engages is racial (or racialist in 19th century parlance) in its mode of thinking. In this way, many paradigms and discourses continue to labor under the legacy of 19th century racialist thought, even if they do not explicitly mention race, identity or nationalism. For me, this is the most appropriate attitude with which to approach the two diagrams I constructed for the exhibit.

Second, the two diagrams I made are temporal traces of the background influence of race thinking on architecture theory. In the first diagram, I note the alternation within biological metaphors for design between sources that explicitly cite research from fields that attempt to place the role of race and racial identity in biological, social and cultural matters versus those that focus upon the formal or morphogenetic principles of biology to the omission of its role in constructing identity as such. In this manner, my work attempts to trace the general tendencies of architectural discourses toward and away from scientific race theory as a critical basis for making substantive judgements about form, national origins, temperaments, etc.

This latter point–providing an explicit basis from which to understand the contributions of racial identity–is important to trace in architectural discourses because they enable readers to identify when designers had a critical vocabulary to discuss racial difference and when they did not, at least in terms of the disciplines and discourses they were in dialogue with. In a personal sense, it is also a visual analogue for the historiographical observations collectively made in Race and Modern Architecture (but perhaps most clearly expressed in Irene Cheng’s essay) that explicit citations of racial identity within modern architecture theories tended to disappear in the twentieth century as international rhetorics sublimated the scientific references that made national architectural styles so influential in the late nineteenth century. We know that racial categorizations as such, and more importantly their social effects, continued beyond this break, but they are far more difficult to trace because of the lack of explicit references to racialist models of difference. During this period, modern architects continued to borrow from disciplines and discourses that did not prepare them to discuss the racial implications of their explicit references to biology.

During the process of making these two diagrams, Curry experimented with transforming the visual trope of the slave ship into a diagram that outlines the cultural expropriations of Black material culture in the discipline of architecture. Each of the diagrams we created collectively expose the specific references that can be found in architectural tectonic theories. What is explicit in Curry’s “Middle Passage” diagram is notes in more bibliographical and paradigmatic terms in my earlier studies. As a triptych, they provide a nuanced reading of the temporal flow of architectural references which coexist as metanarrative in contemporary theory and as new innovations at discreet moments in time.

Our original explanation for this work can be found here on the webpage for e-flux magazine. You can also read an official announcement of the exhibit on the AA’s website here. For the sake of posterity, here are a few images of the final exhibit, which contains a host of brilliant work! Please visit the space if you are in London between now and December 9th when it ends.